The subject of organ trafficking is almost never discussed in the European media. When numbers of victims are compared, it often doesn’t appear to be as pressing a problem as forms of abuse involving forced labour or sex. Despite this, it’s an issue we overlook at our peril: just one individual being exploited for an organ is one victim too many.

LOW SUPPLY AND HIGH DEMAND

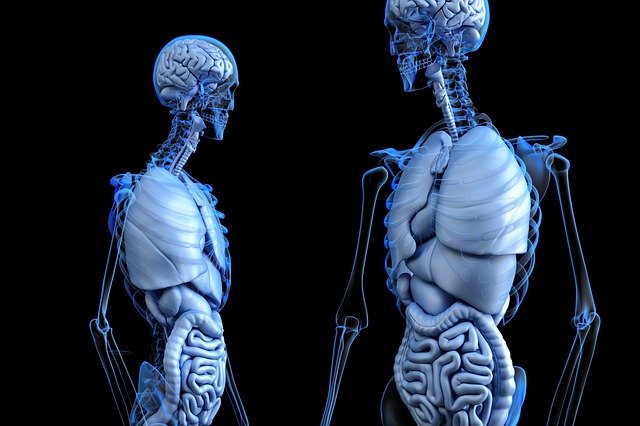

Organ trafficking (often referred to as the “Red Market”) involves the trafficking of human internal organs or other bodily products. These are usually trafficked so they can be used in transplants. According to the figures of the World Health Organisation (WHO), the term “organ trafficking” refers to a commercial transplant which is carried out to generate a profit. Transplants performed outside national healthcare systems are also categorised as organ trafficking, however. Globally, demand for healthy body parts for use in transplants far exceeds available supply, which serves as a motivation for the illicit trade.

When you talk about organ trafficking, there is often outrage at how such a crime could have been allowed to develop. Global Financial Integrity (GFI) estimates that 10 percent of all organ transplants, including those involving human lungs, hearts and livers, are performed using trafficked organs. The best-known illegally trafficked organs, however, are kidneys. The WHO estimates that worldwide, something like 10,000 kidneys are being illicitly trafficked every year – more than one every hour, in other words.

People waiting for an organ donor are either assigned to their relatives or to people who are dying. Sometimes it can take years for a suitable donor to be found, often meaning it is too late for the recipient. In Canada, for example, the average waiting time for a kidney is estimated to be 4 years, while some patients will find themselves waiting for as long as seven years.

ORGAN TRAFFICKING AND HUMAN TRAFFICKING

Organ trafficking is a lucrative, global – and above all illegal – trade. Prices for an organ can far exceed 100 thousand euros . But how exactly is this trade categorised as a crime of human trafficking? The Palermo Protocol of the United Nations of 2000, which provides the foundation for most national laws on people trafficking, defines organ trafficking as part of human trafficking in the following way:

People trafficking “means the recruitment, carriage, shipment, accommodation or reception of persons through the threat or use of violence or other forms of coercion, through kidnapping, fraud, deception, abuse of power or the exploitation of particular vulnerability, or by granting or receiving payments or benefits to gain the consent of a person which involves violence towards another person for the purpose of exploitation. Exploitation includes at least the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labour or forced servitude, slavery or practices similar to slavery, bonded labour or the removal of organs. “

Organ traffickers make their profits in the shadows – often on both sides. As a result, they are endangering not just the donor, but also the recipient, since no emphasis is placed upon finding the right donor. Donors are normally recruited from a position of weakness such as financial need. No importance is attached to the health of the donors, and their organs are often removed under wretched medical conditions. The recipients, on the other hand, can be exposed to life-long health consequences, or even die, if they receive an unsuitable organ in a transplant.

Due to the comparatively low number of victims (compared to sexual abuse and forced labour), organ trafficking is often subject to less discussion. Political decision-makers and general sensitisation campaigns are more likely to focus on trafficking for sex and/or labour. Due to the high demand and relatively low rates of prosecution, however, organ trafficking plays an important role for criminal organisations operating transnationally.

IRAN AND OTHER EXTREMES

Wars and violent conflicts create easy targets for organ traffickers: refugees. Refugees are most sharply exposed to organ trafficking, since they are forced to struggle against hunger, terrible conditions and a highly uncertain future due to their displacement. In 2015, the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) reported its suspicion of organised organ trafficking in Syria, as the number of transplants also rose in neighbouring countries. The protracted conflict in Syria has made the country’s refugee population, which numbers more than 2 million people, easy prey for sex trafficking, removal of organs and forced labour, particularly in Turkey and Lebanon, which, together with Egypt and Libya, are the hotspots of the red market in the region.

Many refugees are desperate, and see no other way out than selling their organs. Organ traffickers are aware of this weak point, and according to reports, are resorting to increasingly harsh means of exploiting it, including kidnapping and murder. In 2013, it was suggested in several reports that Sudanese refugees on Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula were being kidnapped in an effort to generate profits through ransoms. If none is paid, however, the victims are murdered and their organs monetised. In the mortuary of the hospital at Al Arish, human rights activists also found the bodies of deceased people whose organs had been removed. In 2011, activists also reported finding “emptied” bodies in roadside ditches. It is estimated that more than 4,000 people disappeared in the Sinai between 2007 and 2013.

Another hotspot for organ trafficking is China. Standard practice in the country used to be to remove the organs of prison inmates who had been sentenced to death. Even though the legal position no longer permits this, the state still functions as the largest illegal organ trafficker in the country, according to a report by former Canadian Foreign Minister David Kilgour, human rights lawyer David Matas and journalist Ethan Gutmann. The activists estimate that every year, between 60,000 and 100,000 organs are transplanted, with the majority of hearts, livers and other organs used still being obtained by executing political prisoners.

Iran decided upon a different route. In 1988, the government there started its “Lurd” programme. Lurd stands for “Living unrelated renal donation” – the donation of kidneys by living people amongst recipients who are not their relatives. By doing this, it became the first country to legalise this practice. In 1997, this was supplemented by the “Gift of altruism” programme, through which kidney donors receive money and other benefits from the state. To prevent abuse in Iran and abroad, both the donor and the recipient must be Iranian citizens. As a result, there are no long waiting lists for a kidney. Despite this, the ethical discussion over the legalisation of organ trafficking is leading to something similar over sex trafficking, which is essentially legal. The arguments against the sale of organs rest on two general considerations: the sale is a violation of human dignity, and of justice.

Translation by Tim Martinz-Lywood, European Exchange Ltd.

www.european-exchange.co.uk